The Cultural Contexts of the Twentieth-century House and Suburb

[i] Adapted from House and Home: Cultural Contexts, Ontological Roles, Chapter 8, “Domestic Cultures: the twentieth-century house and home,” London: Routledge, 2017, pp. 127-145.

It is an obvious point that the suburban house has occupied a preeminent position in Anglo-American and, particularly, twentieth-century American cultures. What is less obvious are the multitudinous reasons why this is so. Further challenging cogent and dependable analyses are the difficulties of understanding the recent past, or worse, a still developing present, where the volume of information does not naturally lead to the mature understandings more distant histories can sometimes afford. But, it can be confidently stated that house and home as central to people’s lives and identities is a modern, Anglo-American invention. For Greco-Romans home may have been important, but it was secondary to the virtues of public life; aspects of which are recognizable in the histories of European and Latin American cities.[i] This has not been the case in Anglo-American contexts, dating from eighteenth-century England and nineteenth- and twentieth-century America. Temples, civic buildings, markets, and plazas centered the public realm of the Greek and Roman city – but the centers of the suburbanized city are autonomous residential units.[ii]

There are, of course, many reasons for the values ascribed to the twentieth-century house and home. As I will discuss some beliefs and attributions that support its hegemony found early expressions in Imperial Rome, Renaissance Italy, and Georgian England. However, what follows is not a history of the suburban house and its suburban settings, but an explication of its predominant symbolizations and materializations. Like many symbols it is a shape-shifter, adapting to changing contexts without losing potency. But throughout, as recognizable in other house forms and functions, it embodied and expressed the values of self and society that produced it. Initially the suburban villa was presented as providing settings for health and leisure in pastoral settings, and expressed the taste and status of its inhabitants. Later, the suburban house was positioned as the best place for family and children, a means of spiritual and social progress, and a reflection of freedom, privacy, individuality, and self-identity. It also became a symbol of personal autonomy, development, and achievement, as Alain de Botton transparently illustrates when he states that to be considered home the house needs to “embody moods,” provide a “helpful vision of ourselves,” remind us of what “we need,” and aid in the construction of identity.[iii]

Classical Precedents

The English country house was as a particularly potent cultural symbol that was often depicted in literature as organically emerging from the countryside and as a uniquely English foundation of civil society.[iv] Ben Jonson’s poem “To Penshurst,” ostensibly an ode to an aristocratic estate, portrays an Edenic world where the house symbolizes health, repose, culture, and the virtues of a stable, hierarchical society.[v] Until Jonson’s time country estates were the exclusive privilege of the aristocracy who expressed their taste, privilege, beneficence, and power through their houses. Typically, the Classical language was employed, and architectural texts often valorized the virtues of country estates by citing Roman and Italian Renaissance precedents.

The first suburban villas were arguably Roman, the villa suburbanae of the aristocrats of the late republic and early empire. During this time it was expected that aristocrats would maintain country estates, typically located within a twenty-mile radius of Rome in the Apennine foothills or on the coast. Eventually many villas dotted the areas surrounding Rome including, most famously, Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.[vi] Pliny the Younger’s celebrated accounts of his Laurentian and Tuscan villas described places of retreat from the affairs of Rome by a worldly man, where the villa served as a setting for individual development, contemplation, and study.[vii] In his letter to Gallus, Pliny described his seaside, Laurentian villa as just seventeen miles from Rome, but world’s away from its affairs. The Roman poet Martial portrayed the pleasures of the country house as follows.

“You tell me, friend, you much desire to know,

What in my villa can I find to do?

I eat, drink, sing, play, bathe, sleep, eat again,

Or read, or wanton in the Muses train.”

Architects of the Italian Renaissance drew from classical writers in formulating analogous attitudes and traditions regarding the virtues, benefits, and architectural expressions of country estates.[viii] Leon Battista Alberti in De re aedificatoria of 1485 cited Martial to present country houses as places of repose, recreation, and rest. Even though a city house was deemed necessary for conducting business, the country house was required for health and well being. He states,

“The physicians advise us to dwell in the clearest and openest air that we can find; and there is no room to doubt that a country house seated upon an eminence, must of course be the best,” and concludes that there are none “so commodious or so healthy as the villa.”[ix]

Andrea Palladio furthered Alberti’s sentiments in The Four Books of Architecture, first published in 1570. He also mentioned the conveniences of city houses, but described country houses as more healthy and restorative. Recalling Pliny’s reflection that his Tuscan villa promotes “health of body and mind,”[x] he stated that in the country “the body more easily preserves its strength and health,” and “the mind, fatigued by the agitations of the city will be greatly restored and comforted, and be able quietly to attend the studies of letters, and contemplation.”[xi]

Palladio designed the Villa Capra (Rotunda)[xii] as a country retreat for the Venetian Canon Paolo Almerico. The house and grounds, located outside of Vicenza, typified the bucolic estates also built outside Venice, Rome, and Florence by the landed gentry of this time, and the practice of villeggiatura, or withdrawing to the country.[xiii] The surrounding land was not a working farm but a cultivated landscape, surveyed from raised columned loggias on each side of the symmetrically composed house.[xiv] It was actually more a pavilion for entertainment than an extensive villa,[xv] fulfilling Alberti’s validation of “pleasure-houses just without the town.”[xvi] Palladio was one of the more prominent architects in Renaissance Italy but mostly known for his churches. The Villa Rotunda communicated the rationality of Italian Renaissance architecture while also incorporating recognizable church organizations and forms. Its conflation of the ecclesiastical and the domestic was perhaps a matter of the formal prejudices of the architect, but it signaled the quasi-sacred status of the house that was to influence its progeny. Palladio wrote, “The ancient sages used to retire to such places where being oftentimes visited by virtuous friends and relations, having houses, gardens, and such like pleasant places, and above all their virtues, they could easily attain to as much happiness as could be attained here below.”[xvii]

That the Renaissance villa came to have profound formal and stylistic influence is well known, what is less explicit is its contribution to the ideal of the cultured house in nature and its promises of a superior way of life. It was in Renaissance England that Palladian villas came to represent the model of aristocratic country estates, and Georgian aristocratic houses were studiously dependent on them. Lord Burlington’s Chiswick House, built between 1726 and 1729 in suburban London, overtly deployed these recognizable motifs and symbols of status. House styles and symbols have a long history as expressions of status, and in England it was Palladianism that was tasked with this ennobling role. But, perhaps more importantly, similar to the subtle connotation of the sacred to the domestic in Palladio’s villas, Chiswick House’s form and organization, which drew liberally from the Villa Capra, expressed a setting for retreat and contemplation. In fact, it was not a house at all, but a two-story pavilion built to display Richard Boyle, Third Earl of Burlington’s art and library, and solely dedicated to his private affairs and public gatherings. It was characterized as more of a house of the muses, of the Lord’s individual inspirations and, as such, communicated these through the architecture and its setting.[xviii]

Palladio’s villas, idealized through The Four Books of Architecture, distilled Classical notions of ideal dwellings in cultivated landscapes in a manner profoundly influential in Georgian England.[xix] Similar to the Villa Capra, Chiswick House overlooked its surrounding countryside from the porch and windows of its piano nobile, including extensive cultivated gardens of walks, bridges, sculptures, and pavilions. Expressions of aristocratic good taste found particular expression in picturesque gardens, which recalled Roman and Renaissance villa suburbanae. Stourhead, in the Wilshire countryside, is perhaps the consummate example of a remarkably naturalistic cultivated landscape. Along miles of trails, some of which circled a created lake, pavilions that recalled Classical themes appeared – the Pantheon art gallery; the hilltop Temple of Apollo; the Lakeside Temple of Flora; and the Grotto with statues of nymphs and a river god. There was also a “Palladian Bridge” and the rustic counterpoint of a “Gothic Cottage.” The house, set on a hill, with its predictable three-part Palladian façade, serenely surved its surroundings. The exact Classical or literary sources of Stourhead’s gardens have been much debated, but they clearly expressed pedigreed erudition and taste.[xx] The Palladian house, with its grand halls, library, and picture galleries performed similar communicative roles. Throughout the estate, classical sources were recalled and expressed, nodes of repose and contemplation provided, and walks and grounds for restorative recreation available. The juxtaposition of the ideal and the natural – the cultured house in cultivated nature – was a common theme of Georgian villas, which subsequently found expression in the modern suburb’s attempts to reconcile country and city with the suburb.

English Suburbs

Country estates traditionally were the privilege of the aristocracy. However, with the rise of a new mercantile and business middle class in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries for the first time in British society there were wealthy families who had achieved positions of economic and political power through their own entrepreneurship and hard work. No longer was the ability of own properties and houses limited to the landed gentry, but instead were increasingly open to the emerging middle class who exercised their prerogative to build homes that responded to their needs and reflected their new status. The notion of the “self made man” resulted in a building type to serve it – the suburban single-family house. This, in many ways, a radical reconsideration of home, can be understood according to specific historical precedents, some of which the new English middle class were keenly aware of, some they were not.

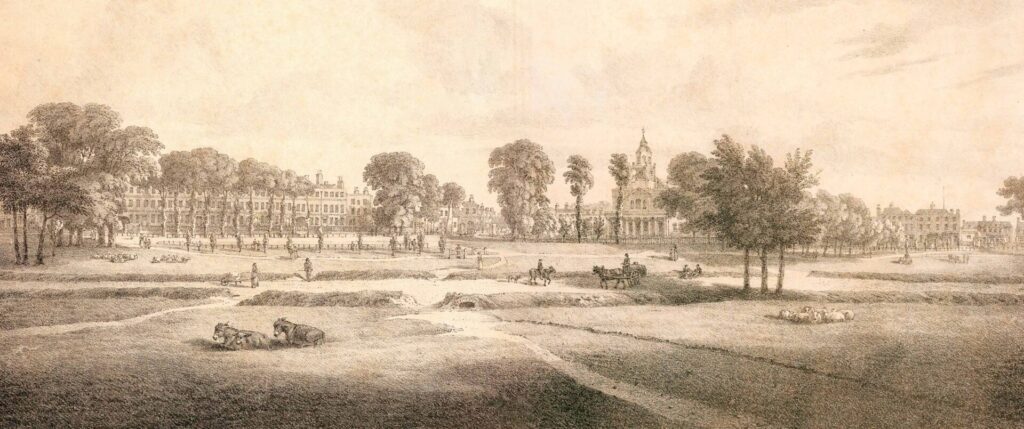

Arguably the first suburbs were built outside of London, where eighteenth-century notions regarding the benefits of healthy, pastoral living, the primacy of the family, the suburbs as a means of spiritual and social improvement, and the house as reflecting one’s social and economic status, coalesced. The Thames river valley outside of London had long been a setting for the country estates of kings and the aristocracy. In Richmond Henry VIII built a palace surrounded by hunting grounds, and nobles such of Lord Burlington built villas not far away. Henry VIII’s palace is gone, but many of the aristocratic estates remain such as Ham House and the Gothic Revival Strawberry Hill. Richmond and its environs were also where the new, bourgeois middle class (who some pejoratively called nouveau riche or parvenu), came to build their own suburban villas and where the confluence of political reforms, available land, and a clientele with the means to purchase homes, coalesced. St. Margaret’s Estate near Richmond, named for the aristocratic owner of a country house and begun in 1854, featured curvilinear streets lined with houses interspersed with private parks. It was built on the banks of the Thames like its aristocratic predecessors, but it was not an estate but an assemblage of modest houses, close to Richmond Green, and convenient to rail travel to London. [xxi]

The new suburbs conveyed the political and monetary gains achieved by this new class by appropriating images of power of the county estates of the aristocracy, while also maintaining the necessary connections to the city – a reconciliation of sorts between country and city. Like St. Margaret’s Estate, early subdivisions often adopted aristocratic names. Victoria Park in Manchester, named for Queen Victoria, was planned by a group of wealthy businessmen as a model suburb.[xxii] It was not a park, but instead featured large houses on curvilinear streets, with a surrounding fence and “toll gates” recalling the country estates of the aristocracy. Opened on July 31, 1837, it was described as providing “the advantage of close proximity to the town with the privacy and advantage of a country residence which, in the rapid conversion of all the former private residences of the town into warehouses, has long been deemed to be a deseratum.”[xxiii] Essential to expressions of the achievement of social status equal to the aristocracy was domestic separation from the “lower classes,” and the dirt, noise, and disease of the industrial city. The early suburbs signaled a gradual but significant change. Previously one’s social position depended only on title or peerage, as the classes freely intermingled in cities such as London and Manchester, now it demanded the physical separation only the new suburbs could provide.

The growing means and influence of the bourgeois precipitated the creation of the first English suburbs. However, ascendant religious beliefs of the Anglican Evangelical movement of this time significantly influenced the values associated with the new suburbs. The Victorians have been credited with defining family, and the home, as an autonomous center of religious and cultural life – the Evangelicals with influencing attitudes regarding new and, presumably improved, domestic settings for families. This moralizing, prescriptive movement was ambitious regarding reforming what they viewed as a shallow Anglican Church and morally corrupt society, with house and home playing predominant roles in affecting the envisioned reforms.

Evangelicals effectively promulgated their strictures through influential publications, which presented home and family as preeminent, leisure activities outside home sinful, and religious devotion, self-denial, hard work, and focus on the family virtuous. Evangelicals had specific ideas regarding what constituted a devout Christian home, and the roles women should play in nurturing it.[xxiv] Contrary to the heterogeneous social and business relationships of the city, they insisted that the nuclear family was the most important social unit. Woman were elevated to head of the Christian home and appointed the leader of religious life while simultaneously separated from opportunities social discourse and power offered by the city.[xxv] One of the Evangelicals’ most prominent spokesmen was William Wilberforce who, in Practical Christianity (1797), argued that women were naturally led to religion, which made them ideal for domestic and nurturing roles.[xxvi] He wrote,

The (female) “sex seems, by the very constitution of its nature, to be more favourably disposed than ours to the feelings and offices of Religion; being thus fitted by the bounty of Providence, the better to execute the important task which devolves on it, of the education of our earliest youth. Doubtless, this more favourable disposition to Religion in the female sex, was graciously designed also to make women doubly valuable in the wedded state: and it seems to afford to the married man the means of rendering an active share in the business of life more compatible than it would otherwise be with the liveliest devotional feelings: that when the husband should return to his family, worn and harassed by worldly cares or professional labours, the wife, habitually preserving a warmer and more unimpaired spirit of devotion, than is perhaps consistent with being immersed in the bustle of life, might revive his languid (lacking vigor) piety, and that the religious impressions of both might derive new force and tenderness from the animating sympathies of conjugal affection.”[xxvii]

Proclamations regarding the corrupting influence of the city were also crucial to their proscriptions. John Newton, a prominent Evangelical, asserted, “Sin overspreads the earth; but in London the number and impunity of offenders, joined with the infidelity and dissipation of the times, makes it a hot-bed or nursery of wickedness.”[xxviii] Cities such as London may have been characterized as degenerate but the new suburbs were promoted as settings where women and children could live a morally superior Christian lives. Of course, the men still had to work in the city, hard work was still a virtue, but family and work now became geographically, socially, and spiritually separated. According to Robert Fishman, the early English suburbs constituted a “radical re-thinking of the relation between the residence and the city,” one in which “exclusion” was its central position – separation from work, commerce, entertainment, lower classes, and other intrinsic elements of the city.[xxix] The men still had access to the diversity offered by the city, including the temptations of its morally compromising elements, but presumably were more able to resist them. Their faith, one can presume, fortified them, but so did the refuge of their religiously consecrated homes. Making use of improved roads and carriages, they commuted to the city, but when their work was done returned to the sanctuary – in all its meanings – of their ideal houses.[xxx]

Clapham in Surry, a London suburb adopted by prominent Evangelicals, epitomized the virtues of untainted family life achieved by the relatively separate location and natural setting of a farming village. Houses ringed a common with a church to serve the “Clapham Sect,” representing the devout family and child-centered environment they desired. Here Evangelicals could live by example –women could perform their duties to family, children, and society, and men could work hard, worship together, and devote themselves to their families. At Clapham a model emerges of exclusive residential enclaves, set in ex-urban settings, and connected to work and commerce by new transportation technologies, which satisfied and expressed religious, cultural, and social imperatives. Even though the twentieth-century suburb that followed was very different, it did reflect some of the priorities of Clapham and its houses.[xxxi] These included the benefits of living with socially and religiously compatible neighbors, house and home as the foundations of a moral society, the suburb as an antidote to the spiritual and physical dangers of the city, and the reconciliation of the private realm of the house and the public through its common setting.[xxxii]

American Counterparts

The American suburban house reflected many of the ideals of its English contemporaries, but found unique expressions in a culture that oscillated between class distinctions and egalitarian self-determination. Its founding fathers built county villas that may have expressed class prestige, but also became national icons of individual achievement. In both cases pastoralism, self-identity, and status found distinct American expressions. George Washington’s Mount Vernon, located on a bluff overlooking the Potomac and within commuting distance of the capital, and Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s rural hilltop villa, came to represent preferred ways of living promised to those who embraced the country’s humanist, progressive democracy. At Monticello Jefferson adopted Palladian planning and style that recalled its aristocratic predecessors (including Chiswick House), without insisting on its exclusivity. Deferring to Palladio’s dictum, his house was “elevated on a cheerful” hilltop in the countryside near Charlottesville, Virginia. Like English estates the offices, or support spaces, are suppressed in deference to the main house. However, it was not a pleasure pavilion or an aristocratic estate, but a working farm that depended on the labor of enslaved people. [xxxiii]

The symbolic content and impact of American houses and homes depended on English precedents and their continental influences. The English had a long history of promoting particular types and styles of domestic architecture. Robert Morris’s Lectures on Architecture (1734-36) popularized the classical style, and his widely disseminated books included specific plans and proportions for houses. However, he also presented the capacity of houses to induce states of contemplation, repose, and insight.[xxxiv] In the seventeenth-century Henry Wotton’s benediction of house and home distilled this personal function.

“Every man’s proper mansion house and home, being the theatre of his hospitality, and seat of self-fruition, the comfortablest part of his own life, the noblest of his sons’ inheritance, a kind of private princedom; nay, to the possessors thereof, an epitome of the whole world.”[xxxv]

John Ruskin in The Seven Lamps of Architecture in 1849 insisted that private houses should reflect one’s character, occupation, and position in society. Not only that, but the correct house was an instrument for self-improvement and necessary for self-fulfillment, and even a lasting memorial to one’s life.[xxxvi] Ruskin also had a bit to say about the home as a refuge and a wife’s role in making it so. “This is the true nature of home – it is a place of Peace; the shelter, not only from all injury, but from all terror, doubt, and division… it is a sacred place, a vestal temple, a temple of the hearth watched over by the Household Gods,” where the “woman’s true place” is that she never sets “herself above her husband, but that she may never fail from his side.”[xxxvii]

Similar to the motivations of their English counterparts some American books on houses and homes also had religious overtones. The influential books of Catherine Beecher whose father, Lyman Beecher, was a member of the Evangelical clergy, not only provided innovations for the single-family house, but also promoted it as a Christian ideal. Women were declared to be in charge of the home and the religious life of the family – echoing the English Evangelicals of a century before.[xxxviii] However, Beecher’s positions were also the product of American religious movements of the time where, according to Claudia Stokes, the home was positioned “as a kind of heaven on earth, a perception that imputes sacred authority to women in creating an environment of happiness that portends that of the millennium and the afterlife.”[xxxix] American idealism was also at play here – a positivist position regarding the potential of individuals to craft their own destiny. Enlightenment sentiments incorporated into the Constitution regarding the equality of all men and their right to pursue their own destiny are illustrative. Horatio Alger’s novels of the mid nineteenth-century and their rags-to-riches themes overtly expressed these attitudes. The crafting an individual destiny, but also the virtues of bucolic settings, were central to the writings of Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson.[xl] Andrew Downing’s popular pattern books on single-family houses, while providing specific plans and styles, insisted on the potential of the house to build and also express one’s character.[xli]

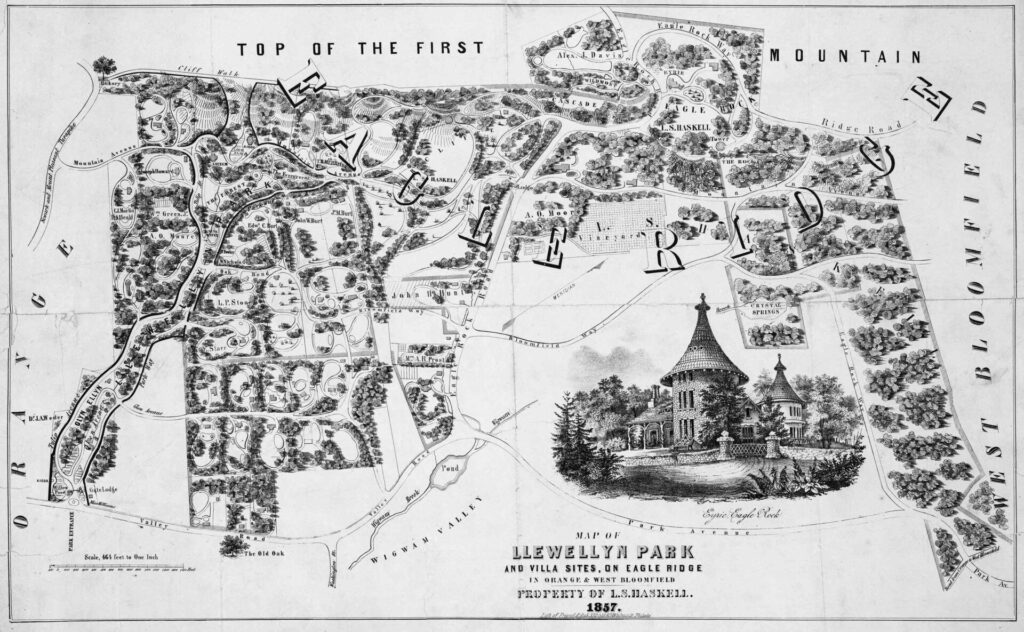

Suburbs composed primarily of single-family houses have proven to be a ubiquitous American development pattern and potent individual and collective symbol. Early American suburban residential developments borrowed freely from their English counterparts with single-family houses, arranged on curvilinear streets, and set in the countryside. Llewellyn Park, in West Orange New Jersey, completed in 1857, has often been referred to as the first planned community in the US. Like St. Margaret’s Estate in Richmond it featured serpentine streets fronted by individual houses and lawns, interspersed with naturalist common greens. Like Victoria Park in Manchester it had a gatehouse. However, unlike its early English predecessors, it was located distant from any civic or commercial areas, an early, single-use subdivision that came to distinguish the American suburbs.[xlii] But, it was also connected to New York City, one hour distant by rail, and thus, while this early gated residential enclave promised a restorative natural setting, it was also connected to the work and commerce upon which the status of its inhabitants depended.

There are certain elements of nostalgia and utopia that define Llewellyn. This could also be said about the planned communities that followed, such as Riverside, located outside of Chicago and designed by Frederick Law Olmstead in 1868.[xliii] Broadacre City, first designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1932 and expanded throughout his career, owes much to Olmstead in its agrarian, naturalistic planning. It also reflects Wright’s philosophy of self-autonomy and self-determination that was informed by his interpretations of American Transcendentalism. Broadacre City was never realized, but Wright’s Usonian houses, designed beginning in the 1930’s, came to represent a certain kind of model of American suburban houses.

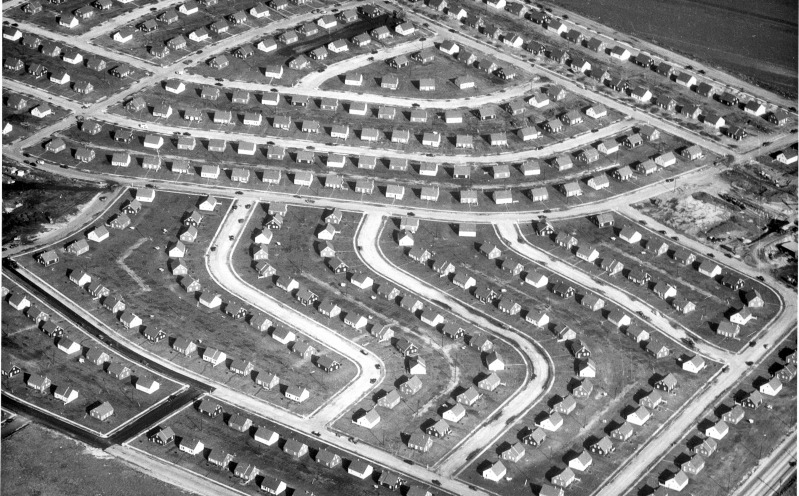

American utopian communities comprise a tangential but relevant context regarding notions of self and community improvement realized through housing and the built environment. They had their genesis in the philosophies and proposals by Charles Fourier who envisioned ideal, communal settlements away from the corrupting influences of the city.[xliv] From Brook Farm, founded by Transcendentalists outside of Boston, to New Harmony, set in the countryside of Indiana, settlements reflected beliefs that the quality and organization of the built environment could improve behavior and society, and support religious life.[xlv] Most utopian communities were short lived. This was not the case with the first Levittown. Built beginning in 1946 by Abraham Levitt and his sons, on farmland in the innocent and bucolic sounding Hicksville, Long Island within commuting distance of New York City, it became the most substantial, and perhaps influential, of the post-war developments. Even though it was far from utopian it did make its own promises for a better life and superior community. Like housing of this time in general it also had political undertones, insisting that home ownership was the foundation of democracy and a bulwark against communism. In the words of William Levitt, “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a communist. He has too much to do.”[xlvi]

Eventually over 17,000 houses were built, the first bought exclusively by veterans, who soon began raising families. It was planned to maximize the number of houses per acre, built efficiently and consistently by employing Fordist standardization and specialization of trades, and sold at competitive prices. Levittown and its progeny achieved what many of the early suburbs promised, albeit in a truncated, distinctly American manner – houses in planned developments, separate from the city and close to nature, which expressed individuality but with a homogeneity of residents that promised a peaceful community and bucolic life ideal for families and children. Its explicit restrictions regarding excluding Jews and African Americans have often been criticized, but they can be understood (though not excused) as a product of the homogeneity suburbs sought to achieve. This was not new – Andrew Downing, an early American proponent of suburban enclaves, penned religiously-imbued bromides regarding their redemptive capacity while also proclaiming that suburban houses were for those who were “largely descended from Anglo-Saxon stock.”[xlvii]

Cultural Priorities and Expressions

Cultures tend to devote resources to what they consider important, either in the form of public support or private enterprises. According to Kenneth Jackson, the suburbanization of America was “as much governmental as a natural process,” and a number of key twentieth-century federal laws and programs proved instrumental to the suburbanization of the country. The National Housing Act of 1934 created the amortized mortgage, which made homeownership much more accessible, and after World War Two federal programs increased mortgage guarantees that enabled and encouraged returning veterans to purchase new single-family houses. Tax benefits supported home ownership and eventually became the nations’s largest federal housing subsidy. Just as new transportation technologies enabled the early English suburb, the late nineteenth-century streetcar in America catalyzed suburban housing developments.[xlviii] Streetcar suburbs were more an outcome of private entrepreneurship than government policy. However, the Interstate Highway System was a remarkable national commitment of resources that had the most profound impact on the American built environment.[xlix] Though its goals were diverse, the result was an economic and transportation infrastructure that supported an unprecedented effusion, and diffusion, of the suburban house and suburbia.[l]

Another effective infrastructure of suburbia was popular culture and especially television, which articulated and enforced the predominant social norms of the time. From its beginnings in England, suburban domesticity was exclusive – suppressing those elements seen as compromising or corrupting to the imagined untainted life it promised. This legacy produced much iteration, with particular inflections in America, where the exclusionary goals of the suburbs took on a particular specificity during the post war period. Suburbia’s dual goals of autonomy and community, epitomized by individual houses linked by shared lawns, proved to have little tolerance for deviations to its scripts of the good life. Television, in particular, was presented as an effective means to establish a common cultural ground, while suppressing discordant voices.[li]

When it came to domesticity the script was predictable and consistent regarding the virtues of the suburban house. The subject was perhaps first introduced by the 1948 film Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, starring Cary Grant, whose comedy-of-errors challenges in building his suburban dream house led to a predictably redemptive and socially affirming ending.[lii] Leave it to Beaver was one of many serialized popular television programs of the late nineteen fifties and early nineteen sixties that presented the virtues of suburban domesticity in an uncomplicated, uncompromising and, one might add, unapologetic manner. The child-centered culture it promoted was appropriately presented by its main character, Beaver Cleaver, and told from “the beaver’s” point of view. Set in the fictitious town of Mayfield, it presented ideals of the suburban house and a white, middle-class world, where the father Ward is the breadwinner and mother June a nurturing stay-at-home mom.[liii] In many ways popular programs of this type illustrated how the social mores and conventions of the post-war period were explicitly delivered through nascent television sit-coms with the suburban house playing a supporting role.[liv]

Criticisms of suburbia have, of course, been around for almost as long as it has. Indeed, it did not take long for popular culture, otherwise an unapologetic cheerleader for suburbia, to present complementary perspectives.[lv] The suburban sitcom presented masculine infused elements of self-determination, individuality, and social improvement, but also ceded this power to a feminized, child-centered domesticity where men are paradoxically absent. Not that this was emancipatory for women, whose choreographed roles were little expanded from the procreative, nurturing, and religious assignments that preceded it. Throughout, the suburban house, like its classical and English predecessors, presented an idealized or, one might say, fictionalized story about the good life and the domestic means to achieve it. In James Ackerman’s words, “The villa accommodates a fantasy which is impervious to reality.”[lvi] Similar to the idealized villa in domesticated nature, the suburban house was the means to control one’s destiny and realize one’s dreams. Like attributes regarding the English aristocratic estate encapsulated by Jonson’s ode to Penshurst, the twentieth-century suburban house was regularly positioned as a foundational and stabilizing component of society. Even though these beliefs were often at variance with their social and economic contexts, and the suburban house eventually deemed to affect just the opposite, the acceptance of these fictions has not substantively diminished.

***

I have argued that cultural proclivities shaped the first English suburbs, the suburbanization of America, and the valorization of the suburban house. The first English suburbs reflected emerging values of its time – for the middle class they satisfied pastoral ideals and class aspirations, for Evangelicals the primacy of the family and the benefits of homogeneous community. These aspects were also present in America but the association of the suburban house with individual freedom, autonomy, and identity assumed particular importance. It is also clear that American suburbanization enjoyed significant federal support and was pursued with at times an evangelical zeal that rivaled the devout builders of the Gothic cathedrals of the Ille de France. America has often been labeled the most religious country in the world. Yes, it may be institutionally religious, but at times it also displays a remarkably religious fervor about issues that matter to it and, like religion, are just as culturally imbedded. Of these the owner-occupied suburban house holds a privileged position. Today the suburban house promises qualities uncannily similar to its Classical and English predecessors. As James Ackerman insightfully observes about the villa generally, “The villa inevitably expresses the mythology that causes it to be built: the attraction to nature, whether stated in engagement or in cool distance, the dialectic of nature and culture or artifice, the prerogatives of privilege and/or power, and national, regional or class pride.”[lvii]

Of course, it is a long and discontinuous path from Rome to the American suburb, but there are also recurring themes of health, pleasure, and family, spiritual and societal progress, status, taste, and the construction and expression of self that have, to greater or lesser degrees, been associated with the suburban house. The ideal of the “self made man,”[lviii] who is able to “hold and transmit property” as a basic right, are enduring American ideals. Home ownership of a house typically serves to represent one’s social and economic class, supported by imagery that bears a remarkable affinity with its English predecessors. The layouts of planned unit developments assiduously adopt symbols of pastoral settings, with curvilinear roads that recall county lanes, and gated entrances reminiscent of aristocratic estates. House models and subdivisions often use English names, paired or portmanteau titles that not only suggest upper class pedigree, but also directly refer to country estates. Names typically conjure images of country farms, hunting estates (park and reserve), or English town, county or country nomenclature. It is a model that has proved to be highly adaptable to changing demographics and gender hierarchies, with each formally disenfranchised group aspiring to own a “home” in a “prestige community.”[lix]

Over time American culture came to prejudice the suburban house at the expense of other housing models. What is euphemistically called the “American Dream” typically means living in a suburban house, and those who own them tend to hold the view that any other housing type will adversely affect the character and value of their community, and those that don’t tend to aspire to own one. Indeed, one’s identity is often conflated with their house to the degree that any perceived threats to the house are viewed as personal attacks.[lx] It is hard not to see religious undertones in these contexts. As I have recognized, religion often informed beliefs regarding the centrality of the family and the capacity of the home to house the self, provide happiness, and express one’s social, economic, and moral status. Indeed, one could argue that not only is a “man’s” home his castle, it is also “his” temple, and as such the center of “his” world.[lxi] An ontological function of the suburban house, especially its early iterations, was to situate self and society. Americans may require self-autonomy and determination, but they also desire connection to others who reflect and support their values. There is also a reassuring hierarchical order in the typical American suburb, where family is the foundation of a stable society and the house reflects status resulting from self-achievements, while its setting evinces a reconciliation of rural autonomy and urban community. These are some of the features that continue to influence and buttress, though often unrecognized, the dominance of the American suburban house, in spite of the dramatic demographic shifts in family make-up, structure, gender equality, and work habits that one might expect would more substantively call it into question than it has to date.

It is clear there are many congruent and conflicting cultural assignations regarding suburban domesticity. The variety of positions of promulgators and critics comprises a broad reception history of the promises and contradictions of the suburban house. All give voice to what the predominant culture values or diminishes; prejudices or dismisses. Similar to other areas of domesticity the house, once again, plays a starring role. Its cultural and ontological roles are a potent mix of appropriations of aristocratic mores, emblems of individual achievement, symbols of religious superiority, and icons of national character. No wonder it has achieved the hegemony it enjoys, despite the fact that it inadequately supplies most of the things it promises. No matter, what is perhaps most important is the phenomenon of the power of the domestic to materialize and communicate a range of class, religious, and cultural beliefs in a manner that has proved to be resistant to the mitigations of the facts of its deficiencies.

[i] Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia, New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, 1987, p. 11.

[ii] According to Robert Fishman, “The true center of this new city is not in some downtown business district but in each residential unit.” Fishman, op. cit., p. 185.

[iii] Alain De Botton, The Architecture of Happiness (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006) p. 107.

[iv] Malcolm Kelsall, The Great Good Place: The Country House and English Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993, p. 7.

[v] According to Richard Gill, “To Penshurst” is a “panegyric to the country house,” where the “natural order of landscape,” reflects the “human order of life inside the house.” Richard Gill, Happy Rural Seat: The English Country House and the Literary Imagination, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972, p. 228. Jonson’s description of the fecund world of nature surrounding the country house has been compared to Martial’s praises of Faustinius’s villa at Baiae. Kelsall, op. cit., p. 15.

[vi] William Macdonald and John A. Pinto, Hadrian’s Villa and Its Legacy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 3-6.

[vii] See John Archer, Architecture and Suburbia: From English Villa to American Dream House, 1690-2000, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005, pp. 35-36.

[viii] Kelsall, op. cit., p. 20.

[ix] Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedificatoria, Book IX, Ch. 2, from Cosimo Bartoli and James Leoni, trans., London: Alec Trianti Ltd., 1755, p. 189.

[x] From Pliny’s Letters on the Tuscan Villa, first century CE.

[xi] Andrea Palladio, The Four Books of Architecture, Book II, Ch. XII, from New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1965, p. 46.

[xii] It was named the Villa Capra after its subsequent owners.

[xiii] Kenneth Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 18.

[xiv] James Ackerman calls it more a belvedere than a villa. James S. Ackerman, Palladio, Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books Inc., 1966, p. 70. See also, James S. Ackerman, The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 106-07.

[xv] Robert Tavernor, Palladio and Palladianism, London: Thames and Hudson, 1991, p. 78.

[xvi] Alberti, op. cit., p. 189.

[xvii] Palladio, op. cit., p. 46.

[xviii] See Archer, op. cit., pp. 58-62.

[xix] Kelsall, op. cit., p. 14.

[xx] Its allusions have been credited to Virgil’s Aeneid, Christianity, sexuality and chastity, and even Henry Hoare’s (its owner and creator) own life. There have even been parsed arguments regarding which passages from the Aeneid were monumentalized. See Stephanie Ross, What Gardens Mean, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998, pp. 63-65, 73-80.

[xxi] See Archer, op. cit., pp. 218-221.

[xxii] See Fishman, op cit., pp. 91-92.

[xxiii] It was not without its critics, one of whom wrote in 1844, “And thus at the very moment when the engines are stopped, and the counting houses are closed, everything which was the thought – the authority – the impulsive force – the moral order of this immense industrial combination, flies from the town, and disappears in an instant. The rich man spreads his couch amidst the beauties of the surrounding country, and abandons the town to the operatives, publicans, mendicants, thieves, and prostitutes, merely taking the precaution to leave behind him a police force, whose duty it is to preserve some little of material order in this pell-mell of society.” Quoted in John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester: An Architectural History, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, p. 38.

[xxiv] See Ian Bradley, The Call to Seriousness: The Evangelical Impact on the Victorians, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1976) pp. 145-154.

[xxv] See Catherine Hall, “The Early Formation of Victorian Domestic Ideology,” in Sandra Burman, Fit Work for Women, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979, p. 25. See also, Fishman, op. cit., pp. 51-62.

[xxvi] According to Catherine Hall, “Central to these new ideas was an emphasis on women as domestic beings, as primarily wives and mothers. Evangelicalism provided one crucial influence on this definition of home and family.” Catherine Hall, “The Early Formation of Victorian Domestic Ideology,” op. cit., p. 15.

[xxvii] William Wilberforce, A Practical View of Christianity, Kevin Charles Belmonte, Ed., (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 1996) pp. 226-27.

[xxviii] Quoted in, Ford K. Brown, Fathers of the Victorians: The Age of Wilberforce, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961, p. 27.

[xxix] Fishman, op. cit., p. 3.

[xxx] The early suburbs benefitted from proximity to London, and regular and efficient transportation.

[xxxi] John R. Gillis, A World of Their Own Making: Myth, Ritual, and the Quest for Family Values (New York: Basic Books, 1996) p. 110.

[xxxii] Commons surrounded by houses of prominent townspeople were to find their own expressions in the New England colonies.

[xxxiii] Jefferson’s rural villa, unlike its Roman and English predecessors of which he was aware, was envisioned as an income-producing farm (though often not a successful one). Like his English contemporaries, Jefferson was an amateur, gentleman architect. For a full discussion of Jefferson and his influences see, James Ackerman, The Villa, op. cit., pp. 185-211.

[xxxiv] Archer, op. cit., p. 49.

[xxxv] Henry Wotton, The Elements of Architecture, (MDCXXIV), London: Gregg International Publishers, 1969, pp. 82-83.

[xxxvi] John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, (1880), New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1989, p. 182.

[xxxvii] John Ruskin, from Sesame and Lilies, “Of Queen’s Gardens,” (1865), in Dinah Birch, ed., John Ruskin, Selected Writings, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 158-59.

[xxxviii] Fishman, op. cit., p. 122.

[xxxix] Claudia Stokes, The Altar at Home: Sentimental Literature and Nineteenth-century American Religion, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014, p. 127.

[xl] Archer, op. cit., pp. 251 and 177 respectively.

[xli] Archer, op. cit., p. 181.

[xlii] See Archer, op. cit., p. 221-24.

[xliii] According to Robert Fishman, “ If there was a single plan that expresses the idea of the bourgeois utopia, it is Olmstead’s Riverside.” Fishman, op. cit., p. 129.

[xliv] This is not an unprecedented claim; William Whyte suggested the same in The Organization Man of 1956. According to Whyte, the new suburbs “bear a resemblance to such utopian ventures as the Oneida Community or the Fourier settlements.” William H. Whyte, Jr., The Organization Man, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956, p. 282.

[xlv] They differ however from the twentieth-century suburbs that followed in that they envisioned self-contained and self-sufficient communities. The 19th century social reformer Ebenezer Howard, credited with founding the Garden City Movement in England, also viewed the countryside as preferable for building a new society. Letchworth, designed by Raymond Unwin according to Howard’s principles, was an early and important prototype that paired housing, shared greenspaces, and industry.

[xlvi] Quoted in Kenneth Jackson, op. cit., p. 231.

[xlvii] A.J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses: Designs for Cottages, Farm –Houses, and Villas, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1850, pp. 268-69. See also, Archer, op. cit., p. 208.

[xlviii] One of the first was Chestnut Hill, outside of Philadelphia, which was conceived by a railroad executive in the late 1870’s as a means to access land for sale and profit. Here, along with a country club, a resort hotel and an Episcopal Church, large houses were set back from the street on large lots.

[xlix] The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 envisioned as an over 42,000-mile system of limited access highways was soon and regularly expanded. Conceptualized by a committee appointed by Dwight Eisenhower, and chaired by a member of the board of directors of GM, its goals were to create a national system of convenient, safe and efficient roads while also providing high volume roads for the evacuation of cities in case of a nuclear attack. Funded by the Highway Trust Fund and funded by gas taxes, which were kept separate from other tax revenues and were non-divertible to other areas, it essentially guaranteed a nearly constant expansion of the nations roads and their upkeep.

[l] According to Kenneth Jackson, “Suburbia has become the quintessential achievement of the United States; it is perhaps more representative of its culture than big cars, tall buildings, or professional football. Jackson, op. cit., p. 4.

[li] Lynn Spigel, “The Suburban Home Companion: Television and the Neighborhood Ideal in Postwar America,” from Beatiz Columina, Ed., Sexuality and Space, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992, p. 193.

[lii] The Money Pit, starring Tom Hanks and Shelly Long, and released in 1986, is a remake of the novel that Mr. Blandings was based on.

[liii] Other characters include the teenagers Wally, the older brother, and Eddie Haskel who serves as the foil for expected behaviors of the time.

[liv] Its predominant themes were more subtly (or subversively) delivered by another popular program, The Munsters, which aired from 1964 to 1966, and was produced by the creators of Leave It to Beaver. Even though the characters of the house are very different from the Cleaver’s, the characters play roles of “monsters,” it presented the same conventions and domesticity as its predecessor. The Munsters are an otherwise typical suburban family who in their struggles to fit in with the social norms of suburbia, illustrate their virtues.

[lv] The reconsiderations of the unitary norms and virtues of suburban domesticity were perhaps presaged by an episode of I Love Lucy, the television show that aired from 1951 to 1957, entitled “Lucy Wants to Move to the Country” when Lucy and Desi move to the suburbs of Connecticut. The episodes that follow highlight the loneliness and dislocation they feel, eventually tempered by, among other things, Fred and Ethel joining them.

[lvi] Ackerman, The Villa, op. cit., p. 9.

[lvii] Ackerman, op. cit., p. 30.

[lviii] The expression “self-made man” was popularized by the Kentucky senator Henry Clay in a speech of 1832.

[lix] It is ironic that prestige is from the Latin praestigiae, which refers to “illusions,” as in magic tricks.

[lx] And, even though multifamily housing is common in suburbia, it is often physically, by its location in peripheral areas determined by zoning, and culturally, “invisible.”

[lxi] Fishman, op. cit., p. 4.