Zoning Reform and Housing Choices

Much needs to be done to create equitable, inclusive, sustainable, healthy, and regionally responsive built environments and housing for those who need it the most. Ultimately, we must build for the future and the common good.

Zoning codes that dominate American land use planning are over 100 years old. In recent years cities across the country have initiated changes eliminating large-lot single-family-only zoning and allowing once-common “missing middle housing.”1 Comprehensive strategies are required to solve 21st century development and housing challenges, of which zoning reform is an integral part. It is an effective way to of create complete communities that are equitable, affordable, sustainable, and walkable,2 and address a full spectrum of issues that many consider important, including:

• climate change, transit, and building a sustainable future

• affordable housing

• justice equity, inclusion, and diversity

• globalization, development, and loss of local character

• health and well-being.

Missing Middle Housing

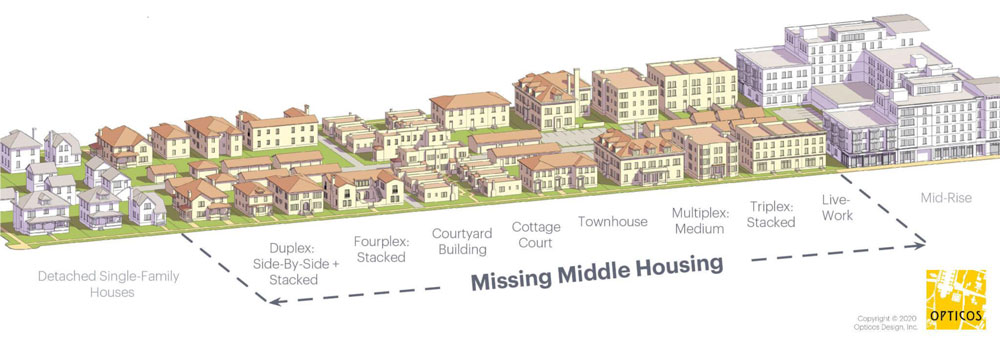

The “missing” in missing middle housing refers to the fact that zoning laws typically prohibit this type of housing. Missing middle housing is diverse housing – it provides choices between single family houses and large apartment buildings including duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhouses, multiplexes, cottage courts, live work and shop houses, and accessory dwelling units. It does not eliminate single family houses but simply provides a broader range of housing types in residential districts to serve diverse housing preferences, ages, household sizes, and income levels.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the single-family house has been the dominant housing type in the US. However, the demographics of the US population are significantly different than they were when single-family focused housing models were enshrined through zoning codes. Today, only 20% of the population comprises “traditional families” of two parents and children. Instead, there is a diversity of family make-ups – from singles to single parents, to multigenerational, same sex, and blended families. It is also an aging population with a growing percentage of those 65 or older. For some, single-family home ownership still works, but for many it doesn’t. Consequently, missing-middle housing responds to the needs of a diverse population and recognizes that individuals, couples, and families need housing choices and that their housing needs change over time. In the 1990s the Congress for the New Urbanism proposed zoning reforms to restore cities, transform suburbs, and protect rural areas.3 More recently, 13 states have initiated legislation to allow missing middle housing, though many have faced significant opposition.4 In 2019 Oregon eliminated single-family zoning for mid to large cities statewide. In 2021 California adopted similar legislation, Connecticut eliminated caps on multifamily housing and legalized ADUs, and Massachusetts adopted the MBTA Communities law that tied state infrastructure funding to by-right, multifamily housing near transit stations.5 A Utah law in 2022 incentivized zoning reform and transit-oriented development through state funding.6 Cities across the country have also implemented zoning reforms that include missing middle housing.7

Climate Change, Transit, and Building a Sustainable Future

A sustainable future depends on skillfully adapting our cities to address 21st century imperatives. Decentralized, carbon-based energy and transportation systems have created unsustainable built environments. It is well established that buildings and transportation are the most significant contributors of CO2 emissions associated with global climate change.8 A “passive urbanism” of compact cities and towns can create transit-oriented development and reduce reliance on automobiles.9

Zoning reform that supports diverse housing choices is essential to creating a sustainable future. It creates gentle density where it is most needed: in inner city and first ring suburbs that are best served by public transit. It also mitigates sprawl and the environmental impacts of auto-centric development and supports public transportation. Smaller units and ones with shared party walls use less materials and require less energy to heat and cool, reducing utility costs, carbon emissions, and an area’s carbon footprint. Compact urbanism, in conjunction with active energy-efficient technologies, such as local energy cogeneration and distribution and buildings as energy producers, are also an effective means to address the multiple issues of global climate change and the built environment.

Affordable Housing

The affordable housing crisis is due to a constellation of issues including a shortfall of housing units, income disparity, and insufficient subsidies. Existing public housing units, affordable housing built with Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits, and rental units subsidized by Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Housing Choice (Section 8) housing vouchers or HUD VASH (Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing) vouchers, are not meeting current needs. Everything else is supplied by the housing market. After decades of diminishing federal support of affordable housing and economically stratified development patterns, broad-based coalitions, public-private partnerships, and zoning reform are required to solve the housing crisis.

Missing middle housing is one piece of the affordable housing puzzle. One effective way to stabilize housing costs is to simply build more housing. Developers are often negatively characterized, but cities are recognizing that they can be allies in addressing the housing crisis.10 By utilizing the private housing market and diversifying housing types and where they can be built, missing middle housing provides housing options to address a worsening national housing crisis. Duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhouses, multiplexes, accessory dwelling units, and cottage courts provide smaller, affordable choices and ownership and equity options – live-work and shop-house units can support home employment. Compact urbanism can reduce household transportation costs – compact housing energy costs. There is no guarantee that the new housing will be affordable, especially in states with weak housing laws. However, many agree that over time as more units are built, housing diversity can open a broader range of housing price points. At best, it produces naturally occurring affordable housing at no cost to municipalities and taxpayers.

Racial and Spatial (In)justice

The recognition of histories of zoning laws used to enforce racial and economic segregation are also driving zoning reforms. The racist government policies that controlled the built environment to suppress Black Americans were just as much civil rights violations as was Jim Crow segregation.11 During the post-World-War-II housing boom, the Federal Housing Administration and GI Bill supported homeownership, but mostly for whites, which significantly contributed to generational wealth disparity. Redlining by banks and government agencies denied loans to Blacks, and deed restrictions limited the purchase and sale of housing to whites. The Civil Rights and Fair Housing Acts of the 1960s were designed to eliminate racism but did not address zoning laws, which have often accomplished what the acts made illegal – racial segregation and economic marginalization. Today, Black Americans are much less likely than whites to own their home and have significantly lower household wealth.

Growing attention to housing discrimination and the affordable housing crisis have spurred land use reform in many cities and states. There is growing consensus that single-family zoning and minimum lot sizes erect economic barriers that prevent lower income people from accessing schools, employment, and services of higher wealth areas. Limited transportation modalities determine the ability of communities to access jobs, schools, and services and often results in missing, scarce, or inflated goods and services in low-wealth communities.12 Zoning reform advocates recognize that the commodification of housing, generational income and wealth disparities, and other social and economic systems have resulted in unequal access to safe, healthy, and affordable housing.

Globalization, Development and Loss of Local Character

Built environments play crucial roles to maintaining cultural memories and identities. Market urbanism,13 placeless sprawl, chain and big-box development, car-dependent transportation infrastructure, and the economically stratified housing of contemporary globalization present diffuse challenges to place and regional identity. Buildings and planned developments may effectively provide for private needs, but rarely contribute to the public good. This is especially true with housing, which is often built by national firms with little interest in the communities where they build.

Missing middle housing is a traditional building type that can support historical continuity. In high growth areas new developments that impact traditional building cultures are inevitable. Inner city residential neighborhoods are often losing character, the result of the market economics of housing development. As land prices rise the only way developers can secure a return on investment is to build either a large house (if that is the only option permitted by zoning), or multiple missing middle housing. Smart cities learn how to guide market-driven growth and regulate the visual character of the built environment. Smaller units refined by form-based codes are more compatible with older residential communities than large, single-family houses or multifamily apartments. Social stability and diversity are supported by housing choices that allow people to age in place and trade down without moving out. The walkable density that results supports local businesses and the smaller scale of missing middle housing can open the market to local housing developers.

Health and Well-being

Walkable communities that provide multi-modal transit choices are healthier places to live. Research has established that compact urbanism results in lower levels of obesity and its associated health impacts. Walkable communities that provide opportunities for impromptu meetings, third places, local businesses, and green spaces support emotional and mental health. Quality, healthy housing for a range of income and wealth levels has direct health benefits for families. Conversely, substandard housing, or auto-dependent exurban housing that requires daily commutes and multiple shopping trips, have many negative health impacts.14

Opposition, Gentrification and Displacement

Zoning reform has sparked opposition to diverse housing and compact, transit-supportive development. Opponents span the political spectrum, cite fears of a loss of character and control of their communities, and share a commitment to maintaining single family zoning. Often the loudest voices have the least to lose in a changing world – they live in affluent neighborhoods and can mount well-funded opposition. This has been the case in many west coast cities where opponents have learned to use zoning and environmental laws to slow or stop affordable housing projects.15 The fiercest battles are often in neighborhoods of single-family houses on large lots close to city centers, services, and public transportation.

Opponents to diversifying housing choices often voice worries that opening the market will result in gentrification. Fears that predatory developers will buy properties in low wealth communities, build market-rate housing, and displace residents, are understandable. Growing cities will experience gentrification, especially in cities where zoning has produced economically stratified settlement patterns. In a market economy limiting units by single-family, large-lot zoning inflates prices making low-wealth areas soft markets for development. Income and wealth disparities amplify the economic segregation of the built environment and the ability of low wealth communities to fight gentrification.

Comprehensive zoning reform can mitigate gentrification of lower wealth communities by creating development opportunities citywide. It is a dependable strategy for producing more units. It’s also simply the right thing to do – everyone needs to do their fair share to address the housing crisis. In supply and demand housing economies, developments that bring the most return on investment may be built first but, as demand ebbs, other price points will open up. The lack of government investment in, or requirements for, affordable housing, results in few effective tools. Consequently, the market may be one of the more effective strategies. Cities with diverse housing can still be unequal, which reveals the significant challenges of providing good housing for all in an economic system that too often perpetuates income and wealth disparity. However, promising research is just emerging that assesses the impact of zoning reform on affordable housing. One recent study concluded, “new market-rate housing construction can improve housing affordability for middle- and low-income households, even in the short run. The effects are diffuse and appear to benefit diverse areas of a metropolitan area.”16 Other recent studies have reached similar conclusions.17

Duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhouses, and multiplexes

Found in older neighborhoods throughout the US. Their smaller units and limited maintenance and landscaping are attractive to the young and old. They create gentle density, walkable neighborhoods, and age and wealth diversity that supports public transportation and local businesses. Their small scale and historical legacy are compatible with residential communities. They also provide equity options. For example, a duplex can be owned by one family who rent the second unit to supplement their mortgage.

Accessory Dwelling Units

(also known as backyard cottages or granny flats), are a historical housing type that used to be common, but beginning in the mid-20th century, became illegal because of zoning changes that legislated single-family houses. They are second, smaller living units typically in an existing house, above a garage, or in the backyards of single-family homes. Like other forms of missing middle housing, ADU’s can be a low impact means of creating housing diversity, particularly in inner city and first ring suburbs. ADU’s can also provide rental income to homeowners that subsidize their mortgage payments making housing they might have been priced out of affordable. ADU’s can also provide stable adaptable housing as family needs and make-up change over time, including rental income when starting out, housing for a parent or boomerang kid, or a unit for a caregiver allowing homeowner to age in place. Homeowners can also live in the ADU as empty nesters, and rent the primary unit, allowing them to trade down without moving out.

Cottage Courts

Small, separate houses clustered around common green spaces, typically with parking located at the perimeter. They are an increasingly popular means to achieve gentle density and attractive to those who want to live in car free environments. Cottage courts can make use of innovative equity and ownership options to reduce housing costs. Community Land Trusts (CLT), which own the land of the cottage court and residents either buy or rent the units. Costs are reduced because one only buys or rents the unit itself, not the land. (There is typically a minimal maintenance fee.) Housing affordability of CLTs is maintained through deed restrictions that limit sale prices while homeowners still build equity. And, because CLTs are always the result of community organizing they often retain their advocacy roles and communitarian framework.

Live Work and Shop Houses

Another ownership and use model that has enjoyed a long history in US cities and towns. A traditional shop house has a street-level retail space with a living unit above. Contemporary uses include home businesses such as beauty salons, accountants, or creative spaces for artists and craftsmen. They can reintroduce neighborhood retail that was once prevalent and create income for homeowners – the building is typically owned by one family who either uses or rents the shop space.

Notes

1 See Daniel Parolek, Ed., Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis, Washington DC: Island Press, 2020

2 See Richard Florida, Bloomberg/CITYLAB, October 2012.

3 Michael Leccese and Kathleen McCormick, eds., Charter of the New Urbanism, New York: McGraw Hill, 1999

4 See Anthony Flint, “The State of Local Zoning: Reforming a Century-Old Approach to Land Use, Land Lines, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 2023, pp. 24-35.

5 David Garcia, Muhammad Alameldin, Ben Metcalf, and William Fulton, “Unlocking the Potential of Missing Middle Housing,” Terner Center Brief, December 2022

6 Anthony Flint, “The State of Local Zoning: Reforming a Century-Old Approach to Land Use, Land Lines, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 2023, pp. 28-29.

7 The Minneapolis 2040 plan is the best known.

8 See Architecture 2030 https://architecture2030.org/

9 Peter Calthorpe, Urbanism in the Time of Climate Change, Washington, DC: Island Press, 2010, 8-24

10 See New York Times, October 16, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/16/nyregion/politicians-housing-crisis-real-estate.html

11 Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017

12 As the urban planner Edward Soja insists, “Justice and injustice are infused into the multiscalar geographies in which we live” and “significantly affect our lives.” Edward J. Soja, Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010

13 Market urbanism is generally minimally regulated commercial development that responds to, capitalizes on, and expresses, market forces.

14 See Harold Frumkin. Environmental Health: From Global to Local. See also: “Health, Equity, and the Built Environment,” Environmental Health Perspectives, May, 2005, p. 113-15

15 See New York Times, June 5, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/05/business/economy/california-housing-crisis-nimby.html

16 Evan Mast, “JUE Insight: The Effect of New Market-Rate Housing Construction on the Low-income Housing Market,” Journal of Urban Economics, July 2021

17 Robert W. Wassmer, Joshua A. Williams, “The Influence of Regulation on Residential Land Prices in United States Metropolitan Areas,”Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 2021

Christina Stacy, Christopher Davis, Yonah Freemark, Lydia Lo, Graham MacDonald, Vivian

Zheng, and Rolf Pendall, “Land-Use Reforms and Housing Costs: Does Allowing for Increased Density Lead to Greater Affordability?”, Urban Studies, March 21, 2023.

Resources

“All About Missing Middle Housing,” Interview by Nathan Spencer of WakeUp Wake County, August 16, 2021