Missing Middle Housing for Raleigh

The “missing” in missing middle housing refers to the fact that zoning laws typically prohibit this type of housing. It includes historic housing types that provide choices between single family houses and large apartment buildings including duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhouses, multiplexes, cottage courts, live work and shop houses, and accessory dwelling units. Missing-middle housing responds to the needs of diverse housing preferences, ages, household sizes, and income levels. It can also create gentle density where it is most needed: in inner city and first ring suburbs.

Missing middle housing does not eliminate single family houses but simply provides a broader range of housing types in residential districts. It can provide affordable housing options to address a worsening national housing crisis. It also supports social stability and diversity and can increase the economic diversity of a community by allowing people to age in place and trade down without moving out. Duplexes, triplexes, quads, and cottage courts provide ownership and equity options – live-work and shop-house units can support home employment.

Missing middle housing is also essential to a sustainable future. It is well established that buildings and transportation are the most significant contributors of CO2 emissions associated with global climate change. Housing density can mitigate sprawl and support public transportation which, along with reducing household transportation costs, can lessen an area’s carbon footprint. Smaller units and ones with shared party walls use less materials and require less energy to heat and cool, reducing utility costs and carbon emissions.

Missing middle housing is part of a national movement of zoning reform to create “complete communities” that are equitable, affordable, sustainable, and walkable. Proponents argue that reforms are needed to create diverse housing and transit-supportive, sustainable development. However, opponents cite fears of a loss of character and control of their communities. The fiercest battles are often in neighborhoods of single-family houses on large lots close to city centers, services, and public transportation. This has routinely been the case in Raleigh.

This studio focused on the research and design of missing middle housing for inner city neighborhoods in Raleigh. Team work included research on missing middle housing histories, policies, and precedents, and sustainable, equitable development and community capacity building. Students worked individually to comprehensively design prototypical housing on a range of sites. The studio as a whole will assembled a diverse knowledge base of housing choices that best serve 21st century Raleigh. A studio research assistant provided additional research and documentation.

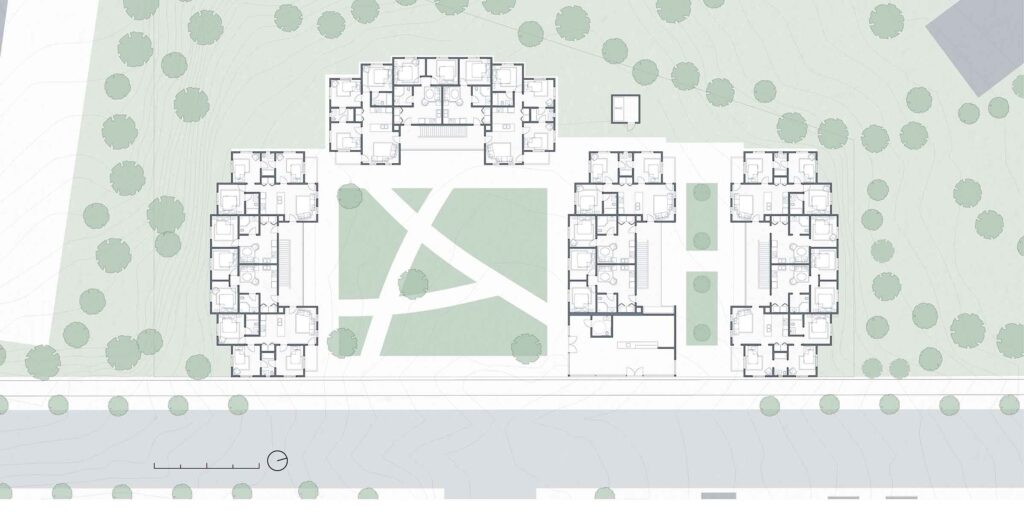

The studio discovered that missing middle housing can capitalize on difficult sites or one’s where only multiple units can provide the sufficient return on investment required by housing developers. The students identified vacant inner-city sites, close to services, schools, and planned or existing public transit and services. The studio collaboratively mapped all potential sites to identify a diversity of sites appropriate to a full range of missing middle housing. The final choices, all of which were in zoning types included in the enabling ordinances, provided specific planning and design challenges. The demonstration projects that follow illustrate the power of design to solve complex planning and design issues and achieve diverse, equitable housing and communities that support transit and local businesses. The results also demonstrated that missing middle housing can also capitalize on sites in critical locations that are missing housing choices necessary for a rapidly growing 21st century city.

Missing Middle Types

Duplexes, triplexes, quads, and townhouses provide options for smaller units with limited maintenance and landscaping tasks that are attractive to the young and old. They can also create gentle density that supports public transportation and local businesses. They can be designed to be compatible with residential communities through form-based codes. They can also provide equity options. For example, a duplex can be owned by one family who rent the second unit to supplement their mortgage or household costs.

Multiplexes are housing with up to twenty units that can maximize sites too big for other missing middle housing but too small for the ubiquitous multifamily housing wrapped around parking. They can also be the most appropriate housing for small or challenging sites that are in higher density and mixed-use districts.

Cottage Courts are multiple units clustered around common green spaces, typically with parking located at the perimeter. They are an increasingly popular means to achieve gentle density, which can support neighborhood retail and services and public transportation. They are also attractive to those who want to live in car free environments. Cottage courts can make use of innovative equity and ownership options to reduce housing costs, such as Community Land Trusts (CLT). A CLT owns the land of the cottage court and residents either buy or rent the units. Because CLTs are always the result of community organizing they often retain their advocacy roles and communitarian framework. They can reduce the price of housing because one only buys or rents the unit itself, not the land. (There is typically a minimal maintenance fee.) Housing affordability of CLTs is maintained through deed restrictions that limit sale prices while owners of a house in a CLT can still build equity.

Live Work and Shop Houses are another ownership and use model that has enjoyed a long history in US cities and towns. A traditional shop house has a street-level retail space with a living unit above. Contemporary uses include home businesses such as beauty salons, accountants, or local crafts, and also creative spaces for artists and craftsmen. The building is typically owned by one family, who either uses or rents the shop space. They can reintroduce neighborhood retail that was once prevalent and create income for homeowners.

Accessory Dwelling Units (also known as backyard cottages, granny flats, etc.) are a historical housing type that used to be common but beginning in the mid-20th c. increasingly were zoned out and thus in many cities are illegal. They are second, smaller living units typically placed in the backyards of single-family homes. Like other forms of missing middle housing, ADU’s can be a low-impact means of creating housing diversity, particularly in inner city and first ring suburbs. ADU’s can also provide rental income to homeowners to subsidize their mortgage payments and thus making housing they might have been priced out of affordable. ADU’s can also provide stable adaptable housing as family needs and make-up change over time, including: rental income when starting out, housing for a parent or boomerang kid, or a unit for a caregiver allowing the homeowner to age in place. The homeowner can also live in the ADU as empty nesters, and rent the primary unit, allowing them to trade down without moving out.

Project Team

Thomas Barrie FAIA: Professor of Architecture

Marina Mustakova: Research Assistant

Guest Critics

Bryan Bell, Danny Garrett, Hattie Gawande, Sara Queen, Michael Stevenson, Jenn Truman, Adam Walters, Patrick Young

Students

CeCe Boudwin, Katherine Brooks, Danytza Cisneros, Jack Dalton, Lakkshita Indrabanu, Emily Lewis, Paige Kanipe, Chelsea Leland, Jennifer MacDonald, Shruthi Manivannan, Lindsay Medbury, Purvij Munshi, Alankrit Ganesh Rajagopalan, Roozbeh Salehi, Veronica Wyatt